Interesting to watch both of Cronenberg’s Crimes next to one another. In an overt way, they have little to do with one another. Maybe some hints in the 2023 film to nod towards the 1970 one. The first an early arthouse outing, filmed silently, with just a voice over. Form steered by budget (or lack thereof). It was Cronenberg’s second film. The second is his latest (hopefully not last), form again seemingly steered by budget. The film is so beautiful, but feels somewhat empty.

In the 1970 film, we follow Adrian Tripod, a director of the House of Skin, a dermatological clinic for wealthy deviants, as he searches through a post-pandemic landscape in search of his mentor, Antoine Rouge, whose experiments caused the disease that wiped all women out. The film broadly shows us where Cronenberg is going to spend the bulk of his career – it’s really an early exploration of the same intersection of body horror and sexuality that will occupy him for most of his life. People afflicted with the disease release a dense fluid from various body parts, nipples, eyes, which Tripod describes as “harmless, even attractive.” The sick body becomes a site of sexual exploration.

As Tripod encounters different characters, his perversions become clearer to the audience. He engages in foot fetishism, each encounter tense with the possibility of violence (which isn’t always the subtext even – sometimes it’s just there). The removal of women leads many men to become deviants, even pedophiles, “a novel sexuality for a novel species of man.” The deprivation of “regular” pleasures leads to the development of new ones. A change in our environment changes the fundamental nature of humanity. This is a key question that will occupy Cronenberg into the future – how much does our changing world change who we are?

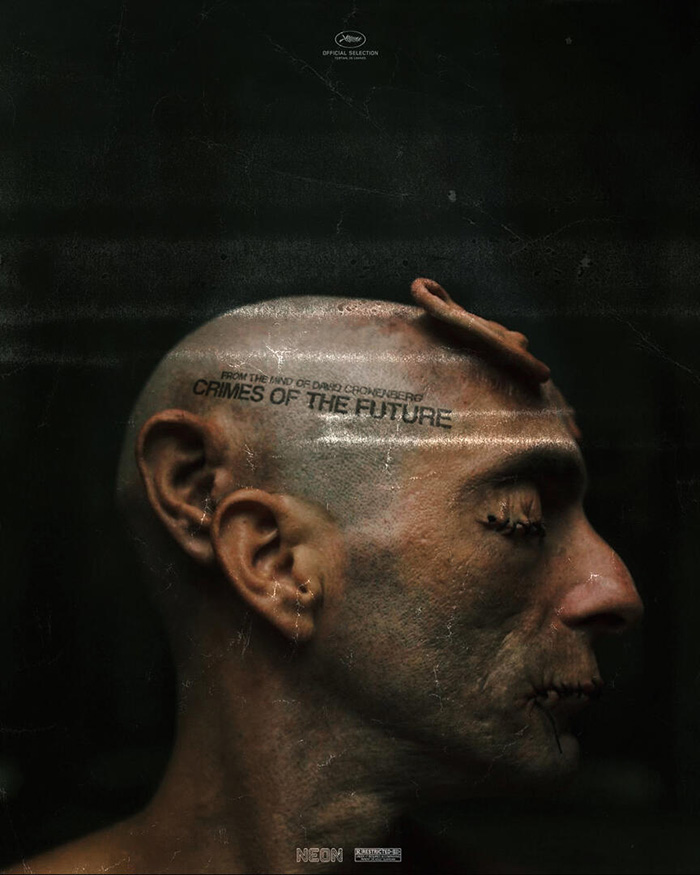

While the 2023 film is not a sequel or a remake, it is in many ways a spiritual continuation of the earlier one, I think. Here, we follow Saul Tenser and Caprice, a world-renowned couple of performing artists. Their art is as follows. Tenser, through some mysterious biological change in his body, is able to grow new organs, with yet undetermined properties and functions. Caprice, an ex-surgeon, uses a repurposed automatic autopsy bed to perform live surgery on him in front of an audience. The question throughout the film is how far can the human body change before it becomes a new species?

This question is most ostentatiously posed by a governmental body called the National Organ Registry. They collect and catalogue new rogue organs, as well as the people who grew them to prevent them from perverting humanity. But humanity is, as the film’s central thesis holds, already perverted. Pain has all but disappeared – Tenser’s surgeries are done without anaesthesia. If there is no pain, pleasure, as we commonly know it, is also gone. “Surgery is the new sex,” we are repeatedly told. In both films our bodily afflictions push our new sexual desires to their logical conclusions.

The only overt reference between the two films is that one of the characters encountered by Tripod in the 1970 film is able to grow new organs, much like Tenser. But the real conversation between them is about what our pleasure reveals to us about our humanity. It’s one that Cronenberg poses elsewhere numerous times, e.g. in Crash (what if car crashes gave you a boner?) or in Videodrome (what if watching tv too much turns you into a monster?).

How far can we go in modifying our bodies before we stop being ourselves? The human question is always close for Cronenberg. He’s interested in exploring our drives and impulses. In the 1970 film, the answer seems to be focused on our sexual drives as requiring a certain balance. On the one hand, our pursuit of beauty is dangerous – the film’s entire world is shaped by a pandemic brought on by beauty treatments; on the other hand, without a pursuit of beauty (here signalled by a lack of women) sexuality becomes perverse (here signalled by the pedophilic gang encountered by Tripod). In the 2023 film the sexual drive is again pulled by the lack of balance – without pain, sex becomes pointless – pleasure in the conventional sense disappears. Instead, the thing we lack replaces pleasure as the focus of our pursuit, so surgery with no anaesthesia replaces sex.

This exploration is perhaps what turns people off the film. In some ways, it’s understanddable – it’s clearly not Cronenberg’s best. In a sense, we could just say, lazily, that this is simply Cronenberg’s shtick. It sort of feels like Cronenberg set out to make a Cronenberg film and was checking off a list of stuff to include: a bit of body horror, some sexual perversion, Viggo Mortensen… I actually don’t disagree with the criticism all that much – the tropes do feel a bit played out. But perhaps this film is meant to be an update. An artist coming back to his early exploration late in life, seeing how differently things might end if he began with a similar premise. If we feel like we’ve seen it before, it’s because we have. The interesting thing isn’t the bit about how our sexuality and humanity intertwine and change, but rather, how this has changed in Cronenberg’s eyes since he was young.

I’m writing this about two weeks after I watched the movies – it’s interesting reading back over the above vis a vis my notes. In my notes, I took the 2023 film to be almost entirely a contemplation about the nature of art – how much control does the artist have over his art? Can Tenser influence the way in which his new organs develop? Yet, this question wasn’t really what stuck with me for the past two weeks as I’ve been planning this reflection in my head. In fact, it hasn’t at all – I wrote it down as a thought while watching the movie and then never thought it again.

At one point one of the characters, I didn’t write down who, tells us that “the creation of art is often associated with pain.” But if Cronenberg is trying to make a serious point about art, it ends up being a bit heavy handed – making art is pain, here’s a guy getting surgery with no anaesthesia to prove this. In the film, art is better understood just as the vehicle for getting us to the question about the venn diagram between pain and our humanity.